An opinion I’ve repeated for as long as I can remember is that any 2 people who want to be together, and want to make their relationship work, can do so. Now, I’m the first to admit that I began to hold this opinion as a teenager without a lot of relationship experience, so there’s bound to be some naivety. Is it completely insane to feel this way, though?

Today, I’m not sure that opinion is 100% accurate without a few caveats; I think that anyone aiming to have a healthy and lasting relationship has a few integral lessons to learn to reach this goal – and to exercise reciprocal patience with their partner along the way.

An extremely beneficial lesson to learn and implement is the concept of “love languages,” made popular today by a 1992 book nearly of the same name: “The Five Love Languages”. Given the sheer volume of material released over the years by the book’s author, Dr. Gary Chapman, I wouldn’t be surprised if the average person writes him off as some sort of charlatan. The religious influence in a lot of his work could be a turn-off to a sizable portion of this generation’s non-religious as well.

I didn’t realize how much criticism this book receives until I started looking for it while working on this Codex entry; but, I really think the book is worth the read – that its lessons are valuable and can improve anyone’s relationship, if even just for its unique perspective. The author is a seasoned marriage counselor and it becomes very clear that he has a lot of professional experience as you work through the book.

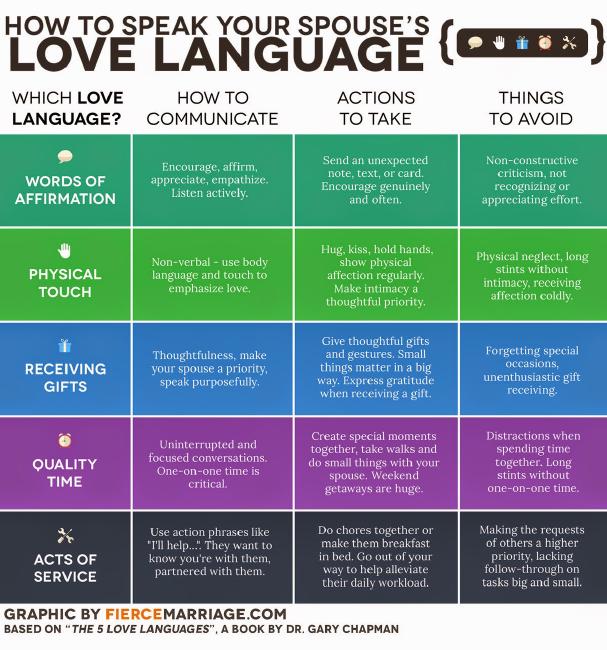

At its core, the book aims to show the reader that everyone has unique ways of expressing and receiving love, and that this can be boiled down into five primary, easy-to-digest “languages.” Those languages are: Words of Affirmation, Acts of Service, Receiving Gifts, Quality Time, and Physical Touch.

At a glance, it’s easy to look at this list and say, “people appreciate all of these things; so what? Isn’t this all obvious?” In that same vein, what inspired me to write about this topic in the first place was a random, seemingly off-topic livestream chat message saying, “love languages don’t exist” – and I could feel the urge to argue bubbling up.

Everyone expresses love differently.

There are examples in the book that illustrate this, and perhaps you’ll also have some relevant memories percolate up with this thought: we all grew up in different families and friend groups that expressed affection or care for one another in different ways. These environments invisibly shaped our expectations of others around us, and these differences are most pronounced in our love life.

image source1

For example, I don’t recall hugging anyone in my immediate family growing up, and it was strange to me when my relatives would hug me before or after an event. Another: it’s completely unheard of to me to end a phone call, or even merely retreat to my room or office for the evening, without saying “love you” to my family or my fiance. Yet there are married couples that never hug or kiss or say “love you” during an average day, and they’re perfectly content with their relationship and no worse off than any other.

As a teenager, I was given plenty of thoughtful gifts or had extremely helpful and memorable favors done for me. Then and now, however, I place an extremely high value on having my personal time and space; like this very moment, in my home office at the end of a work day, relaxing to a phenomenal slushwave album and writing this Codex entry.

Before continuing, perhaps it’s helpful to define these “love languages” more explicitly:

- Words of Affirmation: Verbal expressions of love and appreciation.

- Acts of Service: Doing things to help or ease the burden of the other person.

- Receiving Gifts: Giving and receiving material tokens of affection.

- Quality Time: Focused and uninterrupted time spent together.

- Physical Touch: Physical expressions like hugging, kissing, or holding hands.

“Love languages” are useful, but the book isn’t perfect.

The notion of a “love language” is merely an abstraction of the most common behaviors people exhibit to express affection for one another. The concept itself is undeniably real, though there’s certainly room for disagreement in the prescriptions of the book itself; I’ll even get into a criticism I have of the book:

The book seems to imply, if not state outright, that the vast majority of people have a single “love language,” with some exceptions having two. But, several years ago when my fiance first lent this book to me, I finished it and sparked up a discussion centered around discovering what her love language is. She doesn’t mind me stating this here but her response was essentially “all of them.”

To an extent, she’s not just answering for herself, but for everyone. I mean, sure, there are going to be people who absolutely never participate in Words of Affirmation and aren’t lacking anything in their love life as a result, but it really seems to be the case that everyone “speaks all 5 love languages” to varying degrees; additionally, it doesn’t seem pertinent that an individual in a relationship is able to identify a primary love language, though I can see the clinical benefit in being able to.2

You may already understand or can easily figure out your partner’s and your own love language. It should be more than a guessing game, though, and I heavily encourage you to communicate with your partner. Communication can help ensure that they haven’t simply stopped dropping hints at their love language – such as subtly asking for gifts or quality time together – when you were, intentionally or not, unreceptive. And hey, maybe you or your partner are in the same boat as my fiance, and the answer is “I’ll take all of them, please!” In this case, it’s still helpful to reference back to either the list or the book to ensure that you’re making your partner feel loved.

In any case, it’s still worth the time to ponder and communicate these concepts in the first place so that you may better understand your partner and, possibly more importantly, understand yourself – “knowing yourself is the beginning of all wisdom,” as Aristotle puts it. After all, how can you communicate what you’re looking for in a relationship if you don’t know the answer to that yourself?

the love tank

On the subject of communication, I’ll share one last concept from the book: one’s “love tank.” Simply put, it’s an abstract idea (with a funny name) of how loved someone is feeling in their relationship. The book promotes the behavior of asking your partner how full their love tank is, and if there’s anything you can do to assist.

Perhaps your partner values Quality Time the most, and you’ve developed a routine and typically take Sundays to focus on your own projects. You notice your partner feeling a bit more withdrawn than usual and you ask the “love tank” question. Your partner opens up and shares that they would consider it extremely meaningful and simply explode with joy if you spent focused and uninterrupted quality time together – even if just for a portion of the day. And from my experience, just the act of asking is meaningful and makes my fiance feel loved, even if she doesn’t have a specific ask in mind at that time.

As a final thought, I think the “love tank” concept and question is particularly helpful in American society, where “how are you doing/feeling?” is more of a greeting than a question asked in earnest. The common alternative, however, is point-blank asking how your partner is doing in the relationship, which I feel can come off as potentially “too serious” and anxiety-inducing. “How full is your love tank?” strikes a good balance of being goofy but still serious. The implication of a “low” love tank isn’t that one is feeling unloved in the relationship; rather, that one is temporarily desiring some extra attention in some way.

It’s easy to get caught up in your job or hobbies, but don’t forget to take the time to make sure your partner’s love tank is full by utilizing the five love languages.

c.zip

-

What I’m getting at is that, in a setting like marriage counseling, I can see how it would be helpful to narrow the focus for each individual down to one specific set of behaviors. This can help the couple and the counselor more easily track progress, and make it simpler to make and act on prescriptive requests. ↩︎