codex #4

…and the largest Codex entry to date! I may revisit or refine this argument in the future. I don’t think I’ll ever feel that it’s “done,” but I’ve spent the last week researching and pondering this topic and attempting to put my feelings on it into words. So, it’s time to move on to next week’s topic, whatever that is…

10/01/23 Update

I’ve decided to consider this entry as a sort-of “proto-essay.” I do believe that it does a perfectly fine job of arguing that AI art is art – but by the time I hit “publish,” I realized that I really needed to flesh out a “what is art” framework. I’ve subsequently done so, but there may be some contradictions between the two entries.

AI Art is Art

AI art is, well, art. I think that what most people mean when they say “it’s not art” is something closer to “it’s art but I don’t like it” or “it is objectively bad art.” And really, I feel I can empathize with this point of view the most when I hear a new pop song that seems to only exist to sell a product; I experience a sort of deja vu: “I’ve heard this before, right? This key, these chord progressions, these safe and sanitized sounds, and even the lyrics…” Maybe I’d even make a soon to be out of date joke that this pop song sounds like what you’d get if you asked a robot to write a 2010’s top 40 pop song: cold, lifeless, interchangeable, whatever. But I wouldn’t say that it’s “not art” – I’d say something like “I don’t like it” or “it’s not for me.”

“AI art” now encompasses a lot of stuff, from relatively simple, single-purpose tools to aid an artist, to outright media synthesis. From removing unwanted background noise in an audio recording, to the artist Grimes essentially licensing an AI-generated copy of her voice, to using a short text prompt to generate an image. And now with DALL-E 3 working in tandem with ChatGPT, the ability to even write a prompt is becoming less and less important.

AI Tools

To begin by addressing a topic which has more widespread agreement: AI tools that are generally not used to create a finished piece of art beginning-to-end, but rather only aid in it. Using music as an example, think of something like an AI-powered tool that separates the stems out of a finished song1; perhaps the goal is to create a mashup with one song’s vocals, another song’s guitar, and another’s percussion and bass to create something like a “sound collage.”

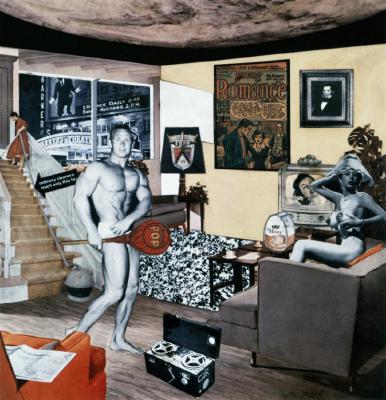

An analogue to this hypothetical sound collage could be the 1956 pop art collage created by Richard Hamilton, “Just what is it that makes today’s homes so different, so appealing?” I understand that pop art has its critics, but if we’re accepting one as art then surely we need to accept both; one artist uses mechanical tools to cut-and-paste images from magazines, recontextualizing them and creating something new as a result, and another artist uses digital tools to work with audio in a similar fashion.

Another example could be an AI-powered tool to master2 a song. Or, similarly, a tool to color correct3 a photograph. Perhaps the artist utilizes the AI mastering tool, or the AI color correcting tool, to get a baseline for subsequent tweaking. In the case of audio mastering, an example could be the bass sounding fine on headphones but being too loud in a car stereo; for color correcting a photograph, maybe the white balance is still a little off and the image has a blue tint as a result.

Again, however, the song or image already exists in the previous examples and these tools are merely being used to enhance them in some way. Because of this, I haven’t seen a lot of controversy around these sorts of AI-powered tools. They serve a very specific purpose and, since they generally wouldn’t be used to create art on their own, they may receive some criticism here and there but there aren’t a lot of serious people arguing that the use of these tools on an art project somehow strips away its artistic merit. But of course, there are much more controversial tools out there…

AI Image Generation as Photography

In the case of image generation, I tend to look back towards photography, which had its own struggles of being accepted as art. It can be fruitful and educational to juxtapose photography and AI art with painting, a unanimously accepted form of art, to ultimately make an argument for AI art’s acceptance.

Photography may be accepted as art now, but a common attitude in the past seemed to be something like: it requires no skill and is entirely mechanical, so therefore it isn’t art. Today, it’s doubtless that both skill and human expression are involved in photography. I see the modern attitude as something like “photography is not painting” rather than “photography is not art.”

Similar to photography becoming its own category, I see AI art as the same: AI-generated art is AI art. Passing it off as a fully-original digital painting, for example, is dishonest and something akin to counterfeiting. However, it wouldn’t be fair to call all AI art as inherently dishonest or counterfeit, so there must be some criteria that delineates the various forms of digital art.

As an example, we wouldn’t say that a photograph of a landscape is a counterfeit of a painting of that same landscape, we would simply call it what it is: a photograph. Even if we load it into a computer and create a digital representation of it, we would still refer to it as a photograph. This has become more obvious as digital representations of photographs have improved alongside advancements in technology, but there was a time when this fact wasn’t as self-evident.

However, let’s say that we crop and color correct the photograph: is this still a photograph? We’d probably call it a digitally-altered photograph if we were being pedantic. But what if we take a drawing tablet and trace over it? What if we add new elements? What if we distort every single pixel in a methodical way, and stretch or morph it to the point where it is completely unrecognizable as a photograph? At this point, we may choose a general term like “digital art,” but that specific detail isn’t important to my broader claim.

AI Art is a New Category

My claim is that we have some general “buckets” we can place art into, but these “buckets” do not have purely objective criteria. I argue in favor of an “AI bucket” much like there is a “photography bucket.” Not every piece of art may fit cleanly into a single bucket, like our chopped-and-screwed4 photograph-turned-“digital art” example, but that doesn’t negate the labels’ validity nor their utility.

I may not be able to draw hard lines around each bucket, but a general rule would go something like: “if the image was predominately created by a camera, and comparatively little human intervention took place, then it would likely be most correct to categorize this art as ‘photography.’” Likewise, “if the image was predominately created by an AI, and comparatively little human intervention took place, then it would likely be most correct to categorize this art as ‘AI-generated.’”

I can hear the disagreement now: “no one is doubting the validity or utility of having an AI-generated category; the argument is that photography is art because it meets certain criteria, while an AI-generated image is not art because it does not meet those same criteria.”

What are those criteria?

There’s obviously more to photography than merely capturing a scene, and there’s more to AI art than simply generating. Like what? What is art?

The Claim

- Curation: how an artist creates

- Skill

- Chance

- Intentionality: the artist’s why

- Interpretation: the audience’s why

Simply put, the argument that I’m building towards is something like: art is created by curation and necessarily requires an artist’s intention and an audience’s interpretation; the artist can also be considered to be the audience as well, however. Curation is how an artist creates art, but there doesn’t need to be just one artist, nor any clear artists at all. Additionally, the intention behind a work of art can be entirely incongruent with the audience’s interpretation of that art.

As stated, though my definition requires an artist’s intention, my concept of an artist is admittedly a little amorphous; a mathematical formula resulting in a fractal may be created entirely without artistic intention or deeper meaning, but the fractal was still “curated” or created by a human (“the artist”) and is still being recognized by an audience for its beauty, for instance.

what makes art, art?

To preface, I want to say that I’m not particularly fond of the term “prompt engineer.” It feels like it implies a similar set of criticisms of photography with a term like “camera engineer.” There’s the implication that the photographer is merely operating a piece of machinery, rather than using the camera as the primary means of creating a piece of art. That said, I think the term “AI artist” can serve as an effective replacement: a painter creates paintings, a photographer captures photographs, an AI artist generates AI art.

Curation: Artist Intervention & How Art Comes To Be

At the core, a photographer and a painter are choosing a subject. This can be for any reason, such as recognizing a particularly exciting or interesting occurrence and aiming and capture or recreate it, or having an idea in their mind’s eye and attempting to manifest it into the physical world.

Monet’s subject was haystacks that were apparently right outside his door. He painted them in different weather and lighting conditions, and it isn’t difficult to imagine a photographer experimenting with the same premise.

Likewise, an AI artist may enter a prompt like “show me Monet’s haystacks in the style of Hieronymous Bosch on a dreary winter day in the early morning” and be met with a handful of options. There’s a particular look that the AI artist enjoys and they choose to generate more and more like it. Ultimately, they practice this once a day, entering 1x prompt returning 8x images, tweaking the prompt slightly to match a description of that day’s local weather and choose different words in an attempt to improve the results. They discard 7 images and choose their favorite.

The photographer is not only participating in curation by choosing to photograph haystacks, but also the time of day and precise angle to take the photo, for example; because of choices the photographer is making, the infinite number of possibilities are being cut down to a finite number; this can be done consciously or not, as a result of skill or chance or, more likely, a never-ending dance between the two.

A painter or an AI artist may be less bound by their physical space, and can choose to create art of something they’ve seen only once – or even art that attempts to capture entirely abstract or fictional concepts with no basis in physical reality.

“How” an artist creates art is through curation, which I’m defining as something like “curation is the choices, both inside and outside of the artist’s control, that an artist influences to aid in the creation of art.” Monet, or a photographer or AI artist essentially mimicking Monet, are all choosing to create art of haystacks, and are all are using different skills to create that art. A painter may need to hone their skills of representing the lighting just right, while a photographer or AI artist may just need to pick the right time of day or modify the prompt in such a way to get the results they’re looking for.

There is the opportunity for exploration, intentional practice, and skill expression in all of these pursuits. The ceiling for skill expression in painting may appear higher than in photography or AI art, but art has never been defined by how difficult it is to create. Anne Frank was simply keeping a diary as countless other young girls have. Banksy’s art generally isn’t showcasing technical prowess. Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square is… literally a black square.

The Dance Between Chance and Skill

Chance is omnipresent in art. Many photographers chose to visit Times Square on V-J Day, but there is only one “V-J Day in Times Square” photograph. Well, perhaps driving this point home, there is actually a second, lesser-known and copyright-free “version” of this photo taken by Victor Jorgensen. The artistic merit of each can be debated, but there is no doubt that they are different photos, both art, and that a not insignificant portion of these differences come from chance.

It’s certainly not all luck, though; Alfred Eisenstaedt, the photographer of “V-J Day in Times Square,” had been a professional, full-time photographer for over 15 years when he captured this famous photo. Assuming all else equal, if he hadn’t preferred natural lighting over flash lighting, nor practiced with smaller, more portable cameras than the press normally did at that time, it’s unlikely he’d have ended up with a photograph with as much impact. The result really speaks for itself.

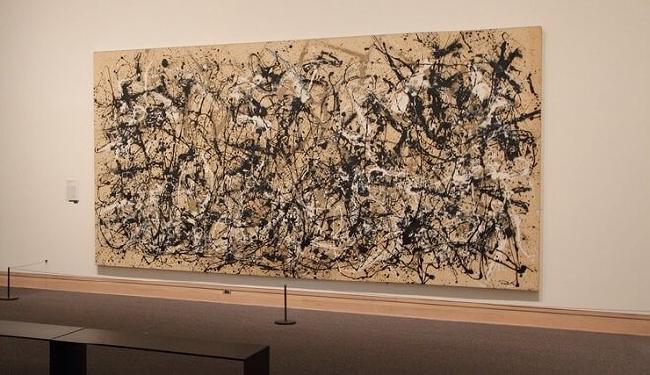

Jackson Pollock has always stressed that his drip paintings are not created by chance and are instead a controlled form of chaos. Clearly, there is plenty of unpredictability and randomness in his work, as is apt to be the case when dripping or throwing paint from a distance. But, even a cursory glance at these works reveals patterns and balance – clear intention.

The work is a record of its process of coming-into-being. Its dynamic visual rhythms and sensation’s buoyant, heavy, graceful, arcing, swirling, pooling lines of color are direct evidence of the very physical choreography of applying the paint with the artist’s new methods. Spontaneity was a critical element. But lack of premeditation should not be confused with ceding control; as Pollock stated, “I can control the flow of paint: there is no accident.”

Perhaps not for the most faint of heart: in the AI art world, there’s Loab. First, this (admittedly creepy) video by Nexpo goes far more in depth about Loab than I will here, and there’s also the artist’s original twitter thread to peruse, but I’ll provide a short version. In essence, the artist Supercomposite accidentally discovered and then further refined a strategy to create some horrific imagery of a unique style, with each image seemingly “haunted” by a recognizable “devastated-looking older woman with defined triangles of rosacea on her cheeks.”

The big lesson for me here with Loab is that image prompting can essentially be used as your custom vector to query the latent space. You can produce novel styles (and characters!) that you literally discover. Negative prompt weighting can help you find emergent accidents, too.

Loab may have been discovered by chance5, but this was a result of deliberate experimentation – not dissimilar to Jackson Pollock developing his progressive style of painting, or Alfred Eisenstaedt’s intentional practice with smaller 35mm cameras and natural lighting.

Artist Intentionality: the why

The artist’s reason for creating a piece of art is possibly the least transparent of the artistic process – at least to the audience’s point of view. As objective as we can try to be, any intention we ascribe to the artist is inevitably colored by our own interpretation of the art.

“V-J Day in Times Square,” for example, can be seen as a cultural icon today, but I think the most charitable and objective view of the artist’s intention must be something like, “Eisenstaedt set out to take photographs that captured America’s feelings about World War 2 coming to an end.” Viewing this through the “curation” lens makes it apparent that, even in this charitable view of the artist’s intentions, Eisenstaedt is still “discovering” what would become an important piece of history and ultimately shape his legacy.

Another, more culturally notorious example worth exploring is the Fountain sculpture by Marcel Duchamp. Duchamp merely flipped a urinal on its side, signed it, and submitted it to the Society of Independent Artists. The artist’s given purpose for his sculpture was, “everyday objects raised to the dignity of a work of art by the artist’s act of choice.” It seems that his intention was as a metacommentary on art itself: to show that an artist’s act of curation alone is how art is made. Stephen Hicks doesn’t feel this was a simply neutral statement by the artist, however:

The artist is a not great creator—Duchamp went shopping at a plumbing store. The artwork is not a special object—it was mass-produced in a factory. The experience of art is not exciting and ennobling—at best it is puzzling and mostly leaves one with a sense of distaste. But over and above that, Duchamp did not select just any ready-made object to display. In selecting the urinal, his message was clear: Art is something you piss on.

Duchamp’s intention of the sculpture may appear to be contrary to my own definition of art, but, in addition to Duchamp’s curation, he also had an intention behind his work. His art ended up finding a sympathetic audience, but it would still be art even if it hadn’t.

To consider a hypothetical AI art example: perhaps an AI artist has an image in their mind that has come to them, night after night, dream after dream. The artist feels as though they’re a vessel for this image. They spend minutes, hours, weeks, months, years writing prompts into an AI image generation app and experimenting with “cross-breeding” AI images with one another.

One day, all of their work pays off: they’re looking at an image that is exactly what they had in their mind all along. The artist’s intention was as self-expression and they feel they’ve achieved it. Even if they share this with others and it means absolutely nothing to anyone but the artist, this is still clearly a work of self-expression and a means of communicating something in the artist’s mind with an audience, even if it has failed to do so.

Audience’s Interpretation

The audience’s interpretation need not align with the artist’s intention to constitute a work as “art” and, at the extreme, art is still art absent an additional audience; the artist is a part of the audience, after all.

Similarly, I would argue that the intutive concept of an “artist” isn’t essential either; an audience can participate in the curation and the imbuing of meaning onto a work of art while having no part whatsoever in its creation. Think something like viewing a snowflake under a microscope and noticing that it looks like a smiley face; it is still art prior to the snowflake’s spectator snapping a photo and making a print; and it is still art prior to the newly-created artist sharing this photo with a broader audience. Later, I will essentially argue that by a human curating this snowflake and recognizing its beauty, not only has the snowflake alone, independent of any photos or prints, been elevated to “art,” but the spectator has been elevated to “artist.” Note, however, that the absence of an artist and an audience means that no curation nor intention nor interpretation is taking place, and therefore there is no art.

A much less charitable point of view of “V-J Day at Times Square” may be that the photograph was strictly taken for record-keeping of the event: this is what Eisenstaedt’s employer wanted, and Eisenstaedt was strictly aiming to further his career or maintain his livelihood. I think there’s plenty of evidence to contradict this pessimistic view of Eisenstaedt, but the photograph would still be art absent the artist’s intention to capture something so profound.

Creating a photograph for record-keeping would still constitute art, in the same way that a painting could be used for the same purpose prior to cameras being invented. Additionally, it may be hard to imagine this photograph being taken completely at random or on accident, absent any intention whatsoever, but an audience viewing this photograph and subsequently imbuing it with meaning would still elevate it from “a photochemical reaction taking place on a strip of transparent plastic material that captures a latent image” to a work of art and potentially even reach its subsequent status as a cultural icon.

A photographer may curate an image of nature, like Frans Lanting visiting all around the globe and capturing stunning photos of the natural world. He is elevating these naturally-occurring scenes to the status of “art” by curating them, much like Duchamp’s urinal. Though in the case of Duchamp’s urinal, meaning is intentionally being imbued onto an everyday object of another individual’s design and creation. In Lanting’s photographs of nature, perhaps there’s an argument that nature is art created by a higher power, but it may be more accurate to view it as Lanting discovering and curating the beauty in nature, similar to Supercomposite’s discovery and curation of Loab.

Another interesting example to consider is Mrs. De Florian’s Paris apartment. It’s obviously not naturally occurring, at least how “natural” is intuitively defined, but it isn’t so clear that Mrs. De Florian is the artist – or that anyone is, for that matter. There are paintings and furniture and wallpaper and plenty of other objects that self-evidently have artistic value, but, similar to Duchamp’s urinal, many of these were everyday items at the time. Their larger meaning seems to come from their greater context as objects used as building blocks for a time capsule of a bygone time.

Entering the untouched, cobweb-filled flat in Paris’ 9th arrondissement, one expert said it was like stumbling into the castle of Sleeping Beauty, where time had stood still since 1900.

Responding to potential criticism

I’ve attempted to provide illustrative examples wherever possible, and stretch my definition to its absolute limit. The most convincing steel man I can come up with to my arguments would probably go something like:

That apartment isn’t art on its own, much like the underlying phenomena that an image is representing is not the art, but the photograph itself is; in other words, the penguins going about their business and having their beautiful colors and patterns being witnessed by a human does not make that event art, rather the resulting photograph of that event is.

Even granting the premise in its entirety, we still end up at photography: the photographer is still operating the art-creating machine, exercising skill while also being at the mercy of chance; participating in curation. The AI art analogue is clear, and just loops us back around to my initial argument for labels or “buckets.” If a photographer is utilizing a camera rather than a paint brush to create art, we would call the resulting art a photograph rather than a painting. In lieu of any other proposed labels, we would similarly refer to AI art as such; still art, but a new category of art.

What is an artist, then?

I’m not completely married to this answer, as I don’t believe it’s required in the greater AI art discussion, but it’s probably simplest to view the artist as “the one who curates.”

In the case of Mrs. De Florian’s apartment, for example, let’s just call her the artist and consider her intention as something like, “to create a beautiful living space.” She curated the apartment using both her own intuition in its contents and organization of those contents; she additionally relied on events outside of her control, such as her being in possession of a Giovanni Boldini painting being heavily influenced by chance.

Everybody’s living space has superfluous objects that have been curated for reasons outside of strict utility. You change your computer’s wallpaper, or buy a mug because you like its design or wanted to commemorate a special occasion; you choose one clock’s design over another or one curtain’s design over another. Even if you could definitively prove that you’ve intentionally curated as minimal a utility-focused living space as possible, it could subsequently be viewed as a statement of personal expression by an audience and be viewed as art – even if it wasn’t intended to be viewed as such.

All of this said, I don’t find the artist’s relationship to their art to be integral to the greater argument. I don’t want to go too deep down this rabbithole, but it’s simple to consider examples where it isn’t clear who the artist is, such as a film with thousands of crew members; or if there doesn’t seem to be any artist at all, such as a phenomena that seems to be an emergent property of the universe, like the Mandelbrot set, or an emergent property of a complex machine, like Loab.

We may say that a photographer is seeking to capture interesting emergent imagery in the world, or someone writing a fractal equation is seeking to capture interesting emergent imagery in mathematics, or an AI artist is seeking to capture interesting emergent imagery from image generating applications. Viewing these individuals as mere observers or audience members who subsequently curate this art would elevate them to artists by the “one who curates” definition.

I’ve also seen the thought experiment of, what if you’re removing your phone from your pocket and accidentally snap a photo; you review your image gallery at a later date and are met with the most beautiful photo you’ve ever seen. Are you the artist? If an artist is “the one who curates,” then I would say yes. But again, the distinction doesn’t really matter; this hypothetical photo is still art whether it’s recognized from the perspective of “the artist” or merely “the audience.”

AI as an artist

At what point does an “artist” status transfer ownership? I don’t consider the answer to this question to be important to the greater AI art argument, but I’ll do my best to answer it because of the criticisms this question leads to.

In many cases, “you know it when you see it.” If I take a photograph and meticulously scramble it beyond all recognition, a reasonable person is unlikely to say that the original photographer is the artist. If we’re being incredibly specific and forthcoming with the art’s origins however, which may even be important to the scrambling artist’s intention and audience’s interpretation of the art, we might split the “artist” credit between the original photographer and the scrambler.

I hear the criticism: “it’s important to know who the artist is because if an image is AI-generated, and isn’t being scrambled or modified, there is no credit for a human. You’re not the artist just because you take someone else’s art and say it’s your own, and you’re not the artist for taking an image from a computer and saying it’s your own.”

We’re back to photography and the Fountain sculpture.

A photographer is manipulating certain inputs on their camera and using it to capture things in the real world. Debating whether or not an architect or a photographer is “the artist” behind a digital image of a building, or what their intentions are with the art is a perfectly fine discussion to have, but just because there isn’t an obvious answer to the question doesn’t make the photograph “not art.” The photographer’s intentions can be minimized in lieu of the architect’s, but the photo’s status as “art” remains untouched. A photograph of nature is similar, where the subject is entirely non-human and the only influence the photographer is exerting is on the capturing of the photo (via curation).

Something similar can be said of the Fountain sculpture. Would not the factory worker or urinal designer be the artist? After all, Duchamp almost quite literally took someone else’s work and slapped his name on it; “I made this.”

The implications of these facts for “AI as an artist” are clear: tracing artwork back to its source may matter for ethical or legal reasons, or even to help interpret the art, but AI artists are still participating in the curation and imbuing of intention onto their art. They may have a much more difficult time arguing that their art deserves an audience considering the common perception that AI art is easy or lazy, much like photography was once viewed, but it is still art just the same.

The Penguins

Finally, to address the earlier penguin example: does a human having a fleeting experience of the natural beauty of these animals count as art? Probably no, at least not under these circumstances alone. This is because there isn’t any human intention whatsoever behind this scene; there is provably no human artist nor intention, unlike in something like a choreographed dance being planned for and performed by humans, and being received and interpretted by an observer.

However, taking a photo of this event would elevate the observer into the artist, as would recording or retelling a story of the experience at a later time. In these examples, the experience is being curated and either intentionally given meaning by the artist, or simply allowing a subsequent audience to develop an interpretation of it. Like in the case of AI art, a human is ultimately participating in the act of curation, and an artist’s intention as simple as “I thought this looked interesting” or “made for a good story” is enough to consider this as art.

In Conclusion

Art

Art is created by the act of curation.

Curation is a dance between skill and chance.

In addition to curation, the only other requirement is that an artist needs to imbue intention onto the art, and an audience (which can merely be the artist) needs to have an interpretation of the art for it to be considered as such.

The intention can be as simple as, “I thought this looked interesting,” or “I wanted to record the happenings of that day.”

An artist’s intention can be entirely incongruent with the audience’s interpretation.

The intuitive definition of art may be as an intentional creation, but art is also frequently discovered or captured.

The intutive definition of an artist is as the creator of a piece of art, and this definition covers many bases. However, things become more and more complicated with multiple “remixes” or generations of a piece of art, or art being curated from a non-human origin and subsequently imbued with intention, such as nature photography or AI art.

AI Art

AI art deserves its own category, similar to photography.

AI art can be as high-effort or as low-effort as any other art form; the act of curation would typically determine effort, but the art is valid as long as any human curation is taking place.

Curation in the context of AI art could mean exercising creativity to come up with interesting prompts, “crossbreeding” images, vigorous experimentation to determine what works best. At the extreme, it could mean coding or training AI software.6

-

A “stem” in this context generally refers to the individual tracks, usually separated by instrument, that make up a full mix. Using an AI tool to separate the stems out of a finished song could allow an artist to manipulate only one instrument, for example, rather than the entire song. ↩︎

-

Mastering is the final process of enhancing and balancing the sonic elements of a mixed song to optimize playback across all devices and media formats. ↩︎

-

Color correction involves adjusting the colors and tones of an image to improve accuracy, balance, and visual appeal. ↩︎

-

Feel free to read the wikipedia page on this music production technique, but in the context of image editing I’m just trying to say that the photograph was remixed and distorted to the point where it would arguably not be considered a photograph anymore. Something similar to vaporwave taking existing music within a clearly-defined genre and modifying and recontextualizing it to such an extent that it would no longer qualify as still being in its original genre. ↩︎

-

There’s some speculation that Loab’s story could be a fictional creepypasta, which might make its existence less “interesting” or intellectually stimulating, but would also arguably mean that its creation required more skill. ↩︎

-

A lot of current AI art seems to be really good at exploring the uncanny valley, and I’m predicting that people in the future will either emulate or attempt to emulate the current AI image generation software. ↩︎